Only a tiny fraction of the writings that survive from Classical antiquity come to us on ancient papyrus (although that number looks to be about to increase). The words of ancient Greece and Rome instead travelled via Byzantium, the Caliphate and the Carolingian world. While that could be spread in the form of copies of complete works, Greco-Roman culture was also transmitted in fragments, sometimes in isolation, sometimes as direct quotation, and sometimes consumed and embedded within the written culture of the time. Much of our classical mythology comes to us in this digested form, never rediscovered simply because it was never entirely forgotten, even if it took on new shapes and purposes.

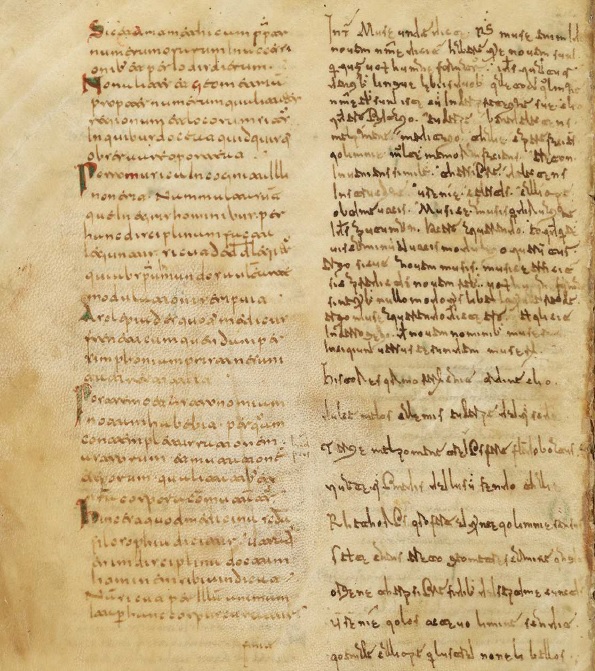

One of my favourite examples of this process in action comes from a note on the Muses in the margin of fol. 36v in Madrid Biblioteca Nacional, MS Vitr. 14–3. I’ll talk a bit more about what it is below, but first here’s a translation based on Juan Gil’s 2020 edition.

Interrogatio et carmen de novem nominibus Musarum, ed. J. Gil, Scriptores Muzarabici saeculi VIII-XI CCCM 65B (Turnhout: Brepols, 2020), 1179-1180.

Question: Where does the name ‘Muse’ come from?

Answer: There are said to be nine names for a Muse, because there are nine things through which the human voice is produced, that is, four teeth, the tongue, the two lips, the palate and the lungs. The names and their meanings are as follows: Clio (i.e. ‘thought’); Euterpe (gladly rejoicing); Melpomene (contemplation); Thalia, (captivating); Polyhymnia (making many memories); Erato (finding a likeness); Terpsichore (delighting in teaching); Urania (the heavenly); Calliope (the best-voiced). ‘Music’ is derived from ‘the Muses’, who were named from apu tu mason, that is ‘seeking’, because from them the power of song and the modulation of the voice are sought. Therefore, just as music is brought about by the nine Muses, so the human voice is produced by the aforesaid nine things, without which no one can speak correctly. Therefore the word ‘Muse’ comes from ‘seeking’.

Here ends the question concerning the nine names of the Muses.

Beginning of verses about those same Muses:

First in order, Clio sings the histories of things.

Euterpe the second gives a sweet strain to the pen.

Melpomene the third brings the tragedians to floods of tears.

Thalia the fourth gives playful speech to comedians.

Polyhymnia the fifth advances rhetorical meaning.

The sixth, singing Erato, composes metrical songs.

Terpsichore the seventh gives melody to all lyres.

Urania the eighth climbs the threshold of the heavens.

Calliope the ninth wanders through all books of poetry.

In classical mythology the Muses were goddesses who provided artistic and philosophical inspiration. References to them appear as early as Hesiod and Homer (‘Tell me, Muse, of the man of many devices’), but it wasn’t until the Hellenistic period that their names, number and areas of responsibility began to be reasonably standardized. (Classics buffs may be looking askance at some of the attributions in the translation above. We’ll get to that below). Ancient poets regularly began their works by invoking the Muses for inspiration. As Christianity became a dominant part of late antique and early medieval culture, that proved increasingly controversial, with poets like Claudian (d. c. 404) and Avitus (d. 517×519) dropping them, while Prudentius (d. 405×413) and Venantius Fortunatus (d. 600×609) replaced them with Christ. Writing in southern England, Aldhelm (d. 709) devoted considerable verse to condemning the Muses altogether. They retained their poetic currency though, with the likes of Dracontius (d. c. 505) calling upon them in his Medea.

Even without the addition we’re concerned with today, Madrid Biblioteca Nacional, MS Vitr. 14–3 is an interesting book. It’s a copy of the ubiquitous early medieval encyclopedia, the Etymologies of Isidore of Seville (d. 636), most likely produced at the end of the eighth or beginning of the ninth century somewhere in al-Andalus. Exactly where is unclear. It first appears in Toledo Cathedral in the eighteenth century, but it seems plausible that it had been there for some time. The betting money is that it was made further south, perhaps in or around Mérida, but that is far from certain. In any case, it is a fine reminder that Christian learning didn’t crash to a halt after the Muslim conquest of the Visigothic kingdom in 711.

Also fascinatingly, the manuscript is filled with short Arabic notes that seem to refer to the text. Although this could be evidence of a Muslim reader, there is plenty of evidence for Christians in medieval al-Andalus who were more comfortable in Arabic than Latin. Here I’m put in mind of the Latin-Arabic glossary contained in Leiden Cod. Or. 231 which, despite being produced in twelfth-century Toledo after the city had been conquered by Castile in 1085, explained Latin terms in Arabic. Interestingly some of these glosses were drawn from earlier Arabic glosses of Isidore’s work, which makes me wonder if Vitr. 14–3 was in Toledo by the twelfth century.

Our little exposition on the Muses has been inserted into a blank space at the end of Book 4 of the Etymologies in the right column of fol. 36v. It is written in a Visigothic cursive that looks tenth-century to my admittedly inexpert eyes. Right from the off it’s a slightly weird text, comparing the nine Muses to the nine parts of the body necessary for speech. Leaving aside the implications that four teeth have for early medieval dentistry, we can identify the source of this analogy, which appears in the Mythologies of Fulgentius. In his great compendium of classical lore, Fulgentius numbered them with Apollo to make ten:

(I.15) For the reason that there are ten organs of articulation for the human voice, whence Apollo is also depicted with a lyre of ten strings… Speech is produced with the four teeth, that is, the ones placed in front, against which the tongue strikes;…two lips like cymbals, suitably modulating the words; the tongue, like a plectrum as with some pliancy it shapes the breathing of the voice; the palate, the dome of which projects the sound; the throat tube, which provides a track for the breath as it is expelled; and the lungs, like a sack of air, exhaling and re-inhaling what is articulated.

Interestingly, Fulgentius also turned to Biblical authority here, referring to the ten-stringed psaltery in Psalms.

The Mythologies circulated in late antique Spain so it is not surprising to see information from it in play here. The etymologies provided in the passage also came from Fulgentius. While he could cite Homer for Clio and Calliope, the origins of the others are decidedly dubious and probably made up by him, as were their roles. For him the Muses were stages of learning, each one building on the previous, beginning with Clio as the initial spur to thought. Calliope had particular significance for Fulgentius. She appears in the Prologue of the Mythologies, bringing him the knowledge that he shares in the work while engaging in increasingly flirtatious and erotically charged banter with him. (To be fair, Fulgentius is seductively quoting Virgil and Terence at her, which I think we can all agree is sexual dynamite.)

The next part of the passage, deriving music from Muse, and Muse from the Greek for ‘Searching’ comes from Isidore’s Etymologies (III.14). This is a garbling of a garbling. The word we have, ‘mason’, is meant to be Isidore’s μάσαι which itself is probably meant to be μώσθαι. The ultimate origin of this etymology is Plato’s Cratylus. Here Socrates engages in debate as to whether names express the fundamental essence of their subject or are merely the product of custom. Along the way he gets asked to explain the names of the gods, leading him to state that ‘the Muses and music in general are named, apparently, from μῶσθαι, searching, and philosophy (406a)’. Socrates (or rather Plato) is being decidedly playful in this section, and we probably shouldn’t take him particularly seriously. It’s thus possible that a moment of philosophical whimsy had become accidentally canonised by the time it reached our manuscript (although I’ve long suspected Isidore of having a sense of humour as well, so perhaps he also understood the tone).

Although I haven’t been able to find an exact origin for the poem, it fits within a longer poetic tradition of praising the Muses. The closest Greek parallel is the anonymous poem 9.504 in the Palatine Anthology, which has the Muses with many of the same attributes in a different order. Latin variants circulated under the name of Cato, linked to the schoolbook tradition of the Dicta Catonis. As this latter connection suggests, simple poems about the Muses were often part of a school curriculum, imparting knowledge of the Classics with practice reading Latin. The Muses here act to transmit knowledge in a much more direct form than that anticipated by Fulgentius.

Although the original bit of Isidore’s Etymologies on page of the manuscript on which this passage appears does not relate directly to the Muses, the heavy emphasis on the meaning of words means it fits in nicely even before we note the quoting of Isidore in the text. It’s not hard to see why a later scribe would think it was a sensible addition. It’s not the only place where apparently out of date information has been added to Vitr. 14–3. At the bottom of the final folio, 163v, someone in the tenth century added a list of Iberian episcopal sees from the pre-Conquest period.

I love this passage because I think it offers a snapshot of how classical culture permeated the early medieval world. Brief snippets of lore from Greek philosophers and Latin clerics were stripped of context and then amalgamated to appear in forms more useable and accessible to Latin (and Arabic) reading audiences. The Muses may be best known for the sudden bursts of inspiration they grant, they great works that come from their blessings. But if she is anywhere, Clio is also here, in the corners of manuscripts, in the translating of tongues, and in the tiny accumulation of details which is how human beings communicate their past to their future.