Thomas Bisson called Catalonia a land of ‘unheroed pasts’. The deep south of the West Frankish kingdom was a land where, for almost three hundred years, historians like Flodoard, Adhemar, or Thietmar were conspicuous by their absence. Nonetheless, I (and many others; these aren’t new thoughts) think we can see a tenth-century tradition of responding to the immediate past of the whole kingdom, and today I’d like to present three texts on that theme.

The first comes from the Abbasid writer al-Masudi, writing in the mid-tenth century. Whilst in Egypt, al-Masudi got hold of a chronicle of the Frankish kings given to the ruler of al-Andalus al-Hakam a few years earlier. The Latin prototype of this text does not survive, but we do have al-Masudi’s Arabic text:

Gotmar of Girona, Chronicle, as given by al-Masudi, The Meadows of Gold, cap. XXXV.

In a book that fell into my hands in Fustat, in Egypt, in the year 336 [=947], given as a gift by ‘Armaz [i.e. Gotmar], bishop of the city of Girona, one of the cities of the Franks, to al-Hakam in 328 [=940]… heir apparent to his father Abd al-Rahman, currently ruler of al-Andalus…

The first king of the Franks was Clovis, and he was a pagan. His wife Clothildis converted him to Christianity. Then his son Clovis ruled after him, then, after Clovis, his son Dagobert ruled. Then after him his son Clovis ruled, then after him his brother Carloman ruled. Then after him his son Charles ruled. Then his son Pippin ruled.

Then Charles son of Pippin ruled, and his reign lasted twenty-six years. This was in the days when al-Hakan was ruler of al-Andalus. After him, his sons fought and disagreements reached the point that the Franks were destroying themselves on account of them.

Then Louis, son of Charles, ruled. He became master of their realm and ruled for twenty-eight years and four months. He was the one who came to Tortosa and besieged it.

After him, Charles, son of Louis, ruled. He is the one who sent gifts to Muhammad [I of al-Andalus]. Muhammad used to be addressed as ‘imam’. His reign lasted for thirty-nine years and nine months.

Then his son Louis ruled for six years.

Then a leader [qa’id] of the Franks named Qumis [= comes, Lat. ‘count’?] rose up against him. He became king of the Franks, and he remained in power for eight years. He made peace with the pagans in regard to his country for seven years, with six hundred rotl of gold and six hundred rotl of silver, to be given to them by the ruler of the Franks.

After him, Charles, son of Taqwira [= ‘of Bavaria’], ruled for four years.

Then after him, another Charles ruled, and he remained for thirty-one years and three months.

Then after him, Louis, son of Charles, ruled, and he is king of the Franks to this day, in the year 336 [=947]. He has ruled the realm for ten years according to the information that has reached us.

[For those of you wondering, hey Fraser, you don’t speak Arabic, how’d you translate this, what I did was, I took an English, French, and Catalan translation, ran the original Arabic through Google Translate, and compared all four, feeding any Arabic words I wanted to dig into into a dictionary. Reader, it took ages, and I could have happily put up König’s translation to much the same effect; but I wanted to be sure…)

This short passage has received a lot of attention, and trying to disentangle it is quite complicated. The Merovingians and early Carolingians are extremely garbled. This is unusual in the Frankish world, where knowledge of this history tends to be pretty good because of the authority of early Carolingian histories and the prime role played by Merovingians in the history of many major abbeys; but makes sense in a Spanish March only really brought under the Frankish aegis in the later eighth century or after.

Then, we have the reign of Charlemagne. The idea that his sons became embroiled in civil war might also seem like a confusion, but it’s not unique to the March: no less educated a tenth-century abbot then Adso of Der placed the Bruderkrieg between Charlemagne’s reign and Louis the Pious’. We then follow smoothly from Louis the Pious to Charles the Bald to Louis the Stammerer. Then we have this ‘Qumis’ figure. This would appear to be King Odo, and indeed the Arabic qa’id nicely captures the ambiguity of the Latin dux, an appropriate descriptor for Odo by the mid-tenth century. Odo is succeeded by Charles, son of Taqwira, who appears to be Charles the Fat; succeeded in turn by Charles the Simple and thence Louis IV. Ralph of Burgundy is, as so often, elided.

Some historians have wished that we had more of this text than what al-Masudi gifts. I think this is all there was, and that it’s fairly faithful; and the best way to show this is to move on. (We will consider this more when we deal with the texts as an ensemble later on.)

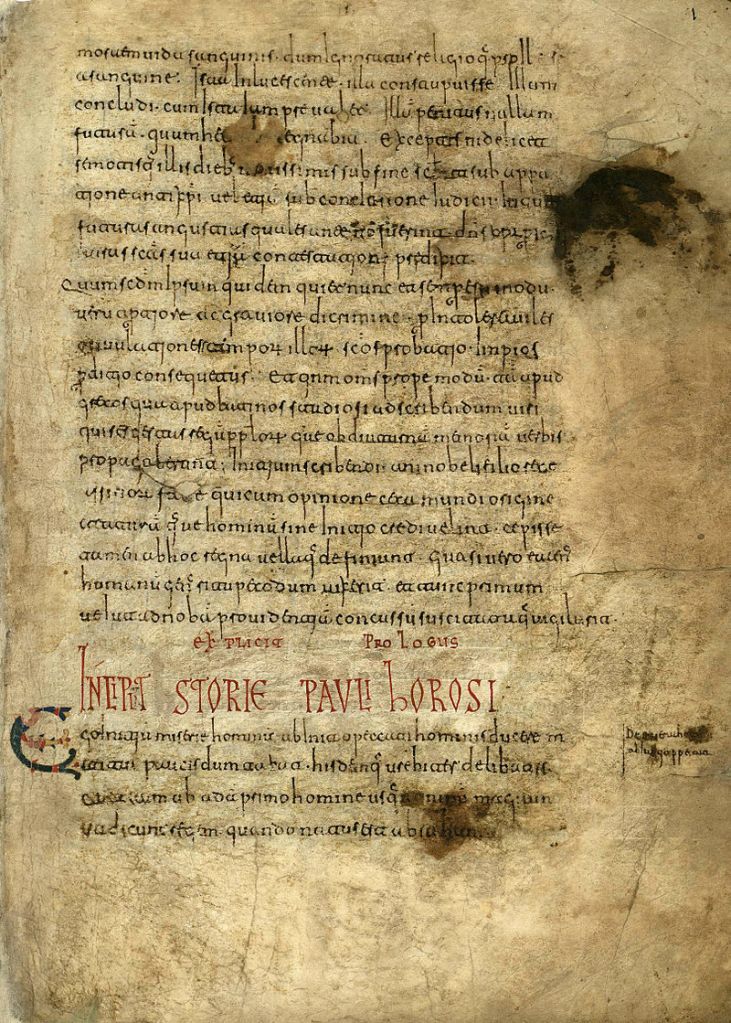

This comes from the Roda Codez (Madrid, Real Academia de la Historia MS 78), a late tenth/early eleventh century book from Navarre. This collection of historical works includes a genealogy of the Frankish kings. It’s not the longest or most complex genealogical text in the work – unsurprisingly, that honour goes to genealogies of the kings of Pamplona and counts of the neighbouring counties. Nonetheless, you may find some of it quite familiar:

De reges Francorum from The Roda Codez, ed. by José Maria Lagarra, ‘Textos navarros del Códice de Roda’, pp. 61-2.

Concerning the Kings of the Franks

I: Emperor Charle[magne] reigned for 48 years and 3 months.

II: Louis, son of the same, reigned for 13 years.

III: King Lothar reigned for 2 years.

IV: Charles, brother of the same, reigned for 38 years and 3 months.

V: Louis his son reigned for 6 years.

VI: Carloman reigned for 6 years.

VII: Charles of Bavaria reigned for 4 years.

VIII: King Odo reigned for 10 years.

IX: After his death, Charles reigned 32 years and 3 months. Then we were without a king for 7 years, after which Louis reigned for 17 years. And afterwards Lothar his son reigned.

If al-Masudi’s text was short, this is even more brief. We’ve lost the Bruderkrieg, anyone before Charlemagne, and all incidental detail other than reign lengths. We’ve also gained Lothar I and a hiatus in place of the reign of Ralph of Burgundy. Let’s leave that fairly bland summary for now, and move onto our final text.

This is a Chronicle of the Kings of the Franks from the Liber iudicum popularis of Bonhom, a judge of Barcelona, around the year 1000. The Liber iudicum popularis was a legal compilation based on the Visigothic law which Bonhom – a figure well-known from charter evidence – composed as a reference guide and update to the older law. The Chronicle here is part of the updated material, framing the law as part of Barcelona’s history, which is a regnal one. The text goes as follows:

Chronicon regum Francorum in Bonhom, Liber iudicum popularis, p. 307

The known years when the lord king Louis took Barcelona. In Era 839 [i.e. A.D. 801], in the reign of the lord emperor Charles, in the 34th year of his ordination as king, his son King Louis entered into the city of Barcelona, having expelled the whole Saracen population (who were keeping it) therefrom.

The aforesaid Charles reigned 47 years and 3 months.

His child Louis reigned for 24 years.

King Lothar reigned for 2 years.

His brother Charles reigned for 39 years and 3 months.

Louis, son of the same, reigned for 6 years.

King Charles the Great reigned for 7 years.

Charles of Bavaria reigned for 4 years.

King Odo reigned for 10 years.

King Charles reigned for 32 years and 3 months.

After his death, they did not have a king for 8 years.

Afterwards, Charles’ child Louis reigned for 19 years.

After his death, his son Lothar reigned for 32 years and 5 months.

After his death, his son Louis reigned for 1 year and 6 months.

Afterwards there reigned Hugh, who had previously been duke, and who snuck his way into a position of rule, and he reigned for 10 years in the realm of the Franks.

After his death, there reigned his son Robert; and he jailed Charles and his sons, who were from the royal family.

[Later additions:

He [Robert] sat in the realm for 36 years.

Henry, his son, reigned for 29 years.

Philip reigned for 49 years.

Louis his son reigned for 29 years.

Louis the Younger reigned for 44.

Philip his son reigned 20.]

*This text can also be found in a Carcassonne manuscript, BNF MS Lat. 5256, with some abbreviations and a different set of later additions.

Again, we don’t have a huge amount of historical information here, but the list and the regnal dates are enough for us to compose a table which will help get a grasp on these texts as a whole:

| Gotmar (length of reign) | Roda Codex (length of reign) | Bonhom (length of reign) |

| Charlemagne (26 years) | Charlemagne (48 years, 3 months) | Charlemagne (47 years, 3 months) |

| <Bruderkrieg> | ||

| Louis the Pious (28 years) | Louis the Pious (13 years) | Louis the Pious (24 years) |

| Lothar I (2 years) | Lothar I (2 years) | |

| Charles the Bald (39 years, 9 months) | Charles the Bald (38 years, 3 months) | Charles the Bald (39 years, 3 months) |

| Louis the Stammerer (6 years) | Louis the Stammerer (6 years) | Louis the Stammerer (6 years) |

| Qumis (8 years) | Charles the Great (7 years) | |

| Charles son of Taqwira (4 years) | Charles of Bavaria (4 years) | Charles of Bavaria (4 years) |

| Odo (10 years) | Odo (10 years) | |

| Charles the Simple (31 years, 3 months) | Charles the Simple (32 years, 3 months) | Charles the Simple (32 years, 3 months) |

| Interregnum (7 years) | Interregnum (8 years) | |

| Louis IV (10 years, up to the present) | Louis IV (17 years) | Louis IV (19 years) |

| Lothar (unspecified, up to the present) | Lothar (32 years, 5 months) Louis V (1 year, 6 months) Hugh Capet (10 years) Robert the Pious (up to the present; later addition: 36 years) |

Putting this data in tandem like this makes me think that all of them represent the same historiographic tradition. The reign lengths given are either identical, or easily accountable by scribal error or slightly different calculations of when the year starts. They also give mostly the same order, including when that order is eccentric. (This, for the record, is why I think Gotmar’s Chronicle wasn’t much longer than what we have, because I think it is an elaborated version of this genealogical tradition rather than a longer text which al-Masudi has abbreviated.) There are a couple of exceptions. The first is the substantial difference in regnal length for Charlemagne and Louis the Pious. Here I think there could be a couple of explanations. On one hand, Gotmar could have dated Charlemagne’s reign to some point based on when he conquered Spain (where Bonhom’s Chronicle begins even if he doesn’t do that with regnal dates); on the other hand, Louis the Pious’ reign as sub-king of Aquitaine during the reign of Charlemagne could be screwing up the calculations somehow. The second point where the texts deviate from each other somewhat are the placing of Qumis in Gotmar and the addition of a Charles the Great, Karolus Magnus, in Bonhom. Qumis’ identity as Odo I think is fairly clear; Karolus Magnus is, I think, Carloman II (r. 879-884). What seems to be happening is that our authors are, in their various ways, getting confused about the genealogical churn of Carolingian rulers between 877 and 888 (I am reasonably sure that the six-year regnal length for Louis the Stammerer comes at least in part from eliding him and his son Louis III). If so, these guys wouldn’t be the only ones.

If these texts do represent different outflows from a more-or-less coherent river of tradition, what can we say about the ideology here? Well, first of all it’s distinctly southern. This is explicit in Bonhom, who starts his account with the conquest of Barcelona (something shared by the so-called Alaó Memorial, a text on the history of the counts of Pallars I chose not to translate); but if I’m right about the odd regnal dating given to Charlemagne in Gotmar’s text, it’s also true there. It is also indicated by the presence of Lothar I. Years ago, I commented that supporters of King Pippin II of Aquitaine against Charles the Baldseem really to have been attached to Lothar, by whom they dated their charters for years after the 843 Treaty of Verdun which divided up the Carolingian Empire; and that he was remembered as ruling in the March suggests a regional affection which persisted into the tenth century.

Lothar I’s presence also hints at the text’s views on dynasticism. Genealogies are inherently dynastic by virtue of being structured by father-to-son descent, but these authors nonetheless find room for Lothar I and Charles the Fat, as well as outright non-Carolingians like Odo, so an uncomplicated Carolingian descent towards the reigning West Frankish monarch such as the West Frankish king Lothar was propagating at this time is not obvious in play. Nonetheless, even if not dynastic per se, there is a clear sense in which the tenth-century Carolingian kings have become the repository of proper regnal order against the high-political disruptions of the time. Charles the Simple is given regnal dates which encompass his entire reign (his coronation as anti-king in 893 to his death in 929, rather than his uncontested reign 898-923), and 929-936 is given as an interregnum rather than allowing Ralph of Burgundy to be king. This broadly tracks with charter evidence, which shows plenty of Catalans at the time acknowledging Charles as king until his death, and then having a very tenuous relationship with Ralph. Then, Hugh Capet and Robert the Pious (especially the former) are treated very snobbishly. Anti-Capetian sentiment in Catalonia wasn’t as widespread or intense as sometimes portrayed – like a lot of West Frankish opposition to the Capetians, it took the form of foot-dragging or snide comments – but the historical texts here track with charter dating clauses such as that which mentioned Hugh ‘who was duke but assumed the beginning of a reign’.

Unheroed as the Spanish March may have been, then, it nonetheless did have a recognisable historical tradition in the tenth century. Would it be great if we had more of it? Yes! Absolutely! Nonetheless, what we have is enough to identify a distinct, regional, approach to the history of the kingdom and a way of caring about the regnal unit of which the March was a part.