Abbo of Fleury was the Hincmar of Rheims of his day, by which I mean that he was mostly a political B-lister but his influence on posterity is massively outsized owing to the substantial preservation of his works. In Abbo’s case, both the volume of his writings and the way they are perceived to harmonise with the demands of eleventh-century reformers make him of considerable interest to historians; yet it is clear that this crusader for the rights of monks against the diocesan bishops was severely hampered by the fact that his diocesan bishop, Arnulf of Orléans, was one of, if not the, most important allies of Hugh Capet. This fact dramatically re-orientated local politics in the Orléanais. Whereas under Lothar Fleury had been influential and close to the king, under Hugh Capet things were different. Arnulf and Abbo both had evident interests in breaking down the other’s authority, and both tried to – hide? Explain? – this in high-flying language of principle; but the fact remains that Arnulf had a lot more to offer Hugh than Abbo had. This was particularly true while Hugh’s war with Odo I of Blois was ongoing:

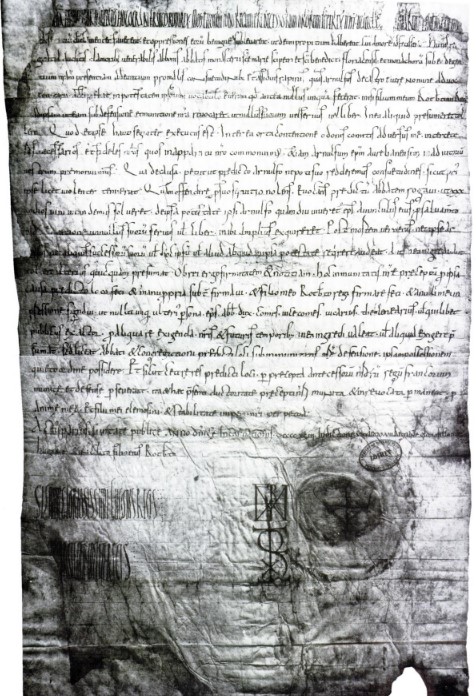

Fleury, no. 70 (993, Paris) = ARTEM, no. 2791

In the name of the holy and indivisible Trinity.

Hugh, by God’s grace king of the Franks.

The custom and habit of the kings Our predecessors was always to elevate God’s churches and clemently favour the just petitions of God’s servants, and to benignly alleviate their oppressions, that they might have God propitious, for love of Whom they did it.

Grace of this matter, having heard the clamours of the venerable Abbo, abbot of the monastery of Notre-Dame, Saint-Pierre and Saint-Benoît of Fleury, and of the monks dwelling under him, approaching Our presence owing to the evil customs and the unremitting rapines which Arnulf of the castle of Yèvre accepted in the name of advocacy and vicariate in their power, named Yèvre, which no-one had ever done before, I sent my son King Robert [the Pious] to it, that he might recall it under Our defence and protection, so that none of his men, whether serf or free, should presume to take anything away therefrom, and he did not execute this at all half-heartedly.

Meanwhile, a contention of Count Odo [I] arose against me, and amongst Our other necessary and faithful men whom We ordered into Our warband, We also summoned Bishop Arnulf of Orléans to Our aid. For this sake, he asked that We might restore these customs to the aforesaid Arnulf, his nephew, as he had previously – albeit violently – held. Unwilling to offend him because of his service, summoning the aforesaid abbot I asked that he should pay 30 pecks of wine from that power at the wine harvest to that Arnulf as long as the bishop his uncle should live, for Our safeguarding, on the condition that none of his men, serf or free, should require anything more there. After his death, let neither Arnulf himself nor any of his successors dare to require this or anything else in that power, or presume to enter into it or to take away anything further.

Therefore, for the confirmation and notice of this matter, I made this precept of Our immunity for the aforesaid place about this case, and I confirmed it below with my own hand, and I had it confirmed by my son King Robert and signed with the impression of my signet, so that no-one else, bishop, abbot, duke, count, viscount, vicar, toll-taker or any public exactor should ever be able to enter in there to exact anything else in Our or future times, or presume to exact anything; rather, the abbot and congregation of the aforesaid place should be permitted to possess that possession in quiet order under the defence of Our immunity and, just as other goods of the aforesaid place should persevere defended and protected through the precepts of Our ancestors the kings of the Franks, so too should this endure protected and irrevocable by the authority of Our present precept, for alms for my soul and my son and the perpetual stability of Our empire.

Enacted publicly at the city of Paris, in the year of the Lord’s Incarnation 993, in the 6th indiction, in the 7th year of the reign of the most glorious King Hugh and his famous son Robert.

Sign of the most glorious King Hugh.

Sign of the famous King Robert.

A note on the text: this act shares an arenga with a forged diploma of Charles the Bald (D CtB, no. ✝480), and the same arenga has clear overlaps with a couple of diplomas of Carloman II for the Spanish March. I presume that something like Carloman’s diploma was the original model; but the problem with Charles’ diploma is that it’s not clear when it was forged (Prou and Vidier, the editor of the Fleury acts, give it a redaction date of the second half of the tenth century at the earliest) and so which direction the influence went is uncertain.

Anyway, what’s interesting about this is the text itself. This was very clearly (in a conclusion emphasised by Levi Roach’s recent analysis of the original’s palaeography) produced in-house at Fleury. The background here is, as I mentioned, the war between Odo I and Hugh Capet. Last we saw, in 991, Odo had been rebuffed at Melun; but conflict was ongoing in 992. The theatre of battle was significant, across almost the whole of the north and west of France: Fulk Nerra of Anjou fought Conan the Crooked of Rennes at Conquereuil, in Brittany; Burchard the Venerable fought Odo himself at Orsay; and Hugh and Robert led a force to Poitiers to besiege Odo’s brother-in-law William Towhead, duke of Aquitaine. The end was a victory on every front: Burchard won at Orsay, Fulk at Conquereuil, and even though Hugh and Robert were unable to take Poitiers they defeated William in battle on the Loire. By winter 992, then, Odo seems to have come to terms with Hugh.

Hugh’s war preparations involved cutting deals, it seems. It is interesting that, per this charter, even Arnulf of Orléans wanted to use his presence in the army to try and cut a deal which favoured his nephew Arnulf of Yèvre, who was disputing control of some revenues with Fleury. This is the kind of source that invites monocle-popping comparisons with eighth- and ninth-century rulers able to summon vast hosts at a click of the fingers as part of their duty towards the state; but these comparisons are overblown. This is, after all, a hostile source. ‘I had to bribe this asshat bishop to get him to come to war and that’s why his nephew gets to keep being evil towards the monks of Fleury’ is the best way of framing this de facto loss if you are a monk of Fleury, but it’s probably not how either Arnulf would have seen it. The letters of friend of the blog Lupus of Ferrières, writing in the early part of Charles the Bald’s reign, hint at similar dynamics of negotiation and patronage, just framed more sympathetically to Lupus-in-Arnulf’s-shoes: in one letter, Lupus flat-out says that he’s too poor to obey a summons to the host and won’t come unless he’s given a subvention.

In fact, it is significant that this diploma exists at all, and the dating clause is an important reason why. The year given is 993, but based on Hugh’s regnal date and the indiction given, we can locate it more precisely to June, July, or August 993. This is well after the end of hostilities, so the deal Hugh struck with the Arnulfs must have been on the order of a year previously. Yet it is only now that it was put into writing. I think that this has to relate to the shifting balance of power between Abbo and Arnulf of Orléans. Originally, it seems, Robert the Pious was sent to kick Arnulf of Yèvre out and restore the monks’ fortunes, but the war allowed Arnulf of Orléans’ influence to wane. Now that the war is over, the monks can try and recover their position, if not by removing Arnulf of Yèvre entirely at least by fixing what he can do so that there’s less space for further exactions. Being allowed to frame the conflict in their own terms was, as Levi suggests, part of the deal, giving them at least a bit of a moral victory.

It is possible to see why the monks might be nostalgic for the previous reign. The bits in italics in the diploma come from the immunities issued for Fleury by Lothar and Louis V. One thing I didn’t comment on at the time, but which is worth revisiting in light of our previous discussion about malae consuetudinesor ‘evil customs’ is that the arengae of the later tenth-century Carolingian immunities framed their discussion of the need for immunities in terms of the evil customs of the wicked, and, rather as in 978 (from a previous abbot of Fleury, no less!), in 993 we have the framing of real events through the discursive lens of an older, theoretical, text. It is in this light important that Arnulf is described as having vicaria. A vicarius was a minor Carolingian official, but vicaria as it developed around the year 1000 were rights for what would later become known as ‘high justice’ (crimes such as arson and murder). This sort of judgement doesn’t seem to be what vicarii did in the Carolingian period, and one can’t help but wonder if it was assigned the name by churchmen in order to relate things they didn’t like to their previously existing immunities…