“Not back on it, Joe, still on it.”

Yep, it’s back once again to the wonderful world of arengae and indeed back again to the specific arenga we’ve already covered on this blog. One thing which happened at the recent International Medieval Congress was that it occurred to me that this arenga, in its ninth-century form, is a nice little illustration of something I bang on about a fair bit, which is the portability of Carolingian ideology. So let’s revisit the spread of this prologue to illustrate that.

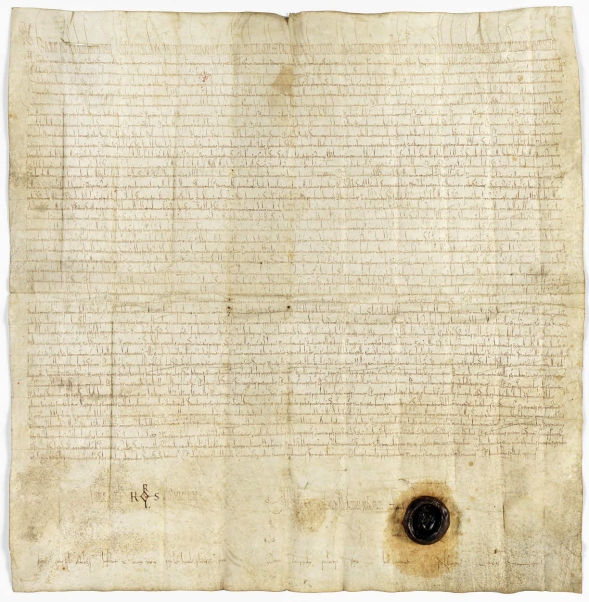

In 862, King Charles the Bald’s long-standing ally Abbot Louis of Saint-Denis was looking to make a very substantial settlement of his abbey’s administration, fixing the revenues available to the monks versus those available to the abbot. To mark the occasion, someone in the royal chancery – over which Louis presided as archchancellor – came up with a new prologue to the royal diploma formalising the split, as follows:

If We confirm by Our edicts that which Our predecessors, by the ordination of divine providence endowed with regal sublimity and illuminated with celestial honour and stirred up by the devoted admonition and prayers of those faithful to the holy Church of God and to them, decreed be established for the state and convenience of churches and servants of God, and if We consent to their most devoted dispositions and carry out the same most pious gifts to the Lord, We believe that this will far from doubt benefit Us in eternal blessing and the tutelage of the entire realm committed to Us by God, and We are confident that the Lord will repay Us in future…

It’s pretty fancy, fancy enough to be recognisable, but the sentiment is conventional. It served its purpose for a more-literary-than-usual introduction to a particularly solemn act, and there it rested for five years. At that time, in 867, with Louis dead, his successor as archchancellor, who also happened to be his half-brother, Gozlin, was doing something very similar at the abbey of Saint-Vaast, in Arras. Evidently he, or a member of his entourage, decided this was an appropriately formal occasion to dust off the old prologue, and so it shows up again here.* Five years after that, Gozlin did the same for another one of his abbeys, Saint-Germain-des-Prés. The final diploma with this prologue, that to the cathedral of Rouen we mentioned before, was also issued around this time.

Not a huge number, but a revealing case. What we have here is an example of a prologue invented for one particular circumstance at Saint-Denis being re-used for no fewer than three other institutions, one also Parisian but the other two in what would become Normandy and southern Flanders. We can see (except perhaps in the Rouen case) fairly clearly how they spread, but what’s more striking is that they could. Charles the Bald and his court could issue diplomas for recipients in such diverse areas in the same language with no problems.

A century or more later, this would not be the case. Normandy, Flanders, and Paris spoke about how and why their rulers were legitimate in very different ways – you couldn’t easily port something as regionally-specific as Norman identity to the heartland of Capetian rule at Saint-Denis. In the ninth century, by contrast, there is a much more coherent idea of legitimate rule at play, which speaks to people in all these different places, and means that a king and his followers can talk to Saint-Vaast like it’s Rouen and Rouen like it’s Paris.

*Actually many of these have minor variations, but they’re all recognisably from the same stem.

3 thoughts on “The Spread of a Charter Prologue”